Frictional Coefficients

The frictional coefficient represents the proportionality between a particle's velocity and its frictional resistance. Frictional resistance is experienced by a particle as it moves through a fluid, either by the influence of an applied force or by Brownian motion.

First, let us consider the \(translational~frictional~coefficitent,~ f_{t}\):

This equation represents the porportionality constant between the velocity of a particle, \(\bf{v}\), and the frictional force that resists that motion, \(\bf{F}_{f}\).

Secondly, we have the \(rotational~fictional~coefficient,~f_{r}\):

This equation represents the proportionality constant between the angular velocity of the particle, \(\omega\), and the frictional torque that resists that motion, \(\bf{T}_{r}\). The particles rotation is applied by either an apllied electric or hydrodynamic flow field or by the diffusion of molecular axes.

\(\textbf{VISCOSITY}\)

Lorem Ipsum

\(\textbf{SPHERES}\)

Frictional coefficents depend on molecular size and shape for a sphere. For example, if we take a sphere of radius, \(R\), and volume

it will have the translational and rotational frictional coefficients:

The equation of the translational frictional coefficent is also known as \(Stokes'~ Law\), and the hydrodynamic radius \(R\) is often referred to as \(Stokes\) \(radius\). Note how the translational frictional ratio is much less sensitve to molecular dimensions than the rotational frictional coefficient.

\(\textbf{ELLIPSOIDS OF REVOLUTION AND CLYINDERS}\)

\(\textbf{RANDOM COILS}\)

\(\textbf{OLIGOMERIC ARRAYS OF SHPERES}\)

Partial Specific Volume

The partial specific volume (PSV or \(\bar\nu\))of a molecule is the inverse of its density (volume required for 1 gram of solute). When in a solution, the \(\bar\nu\) value will inclue the bound solvent that migrates with the molecule in a sedimentation or diffusion experiment.

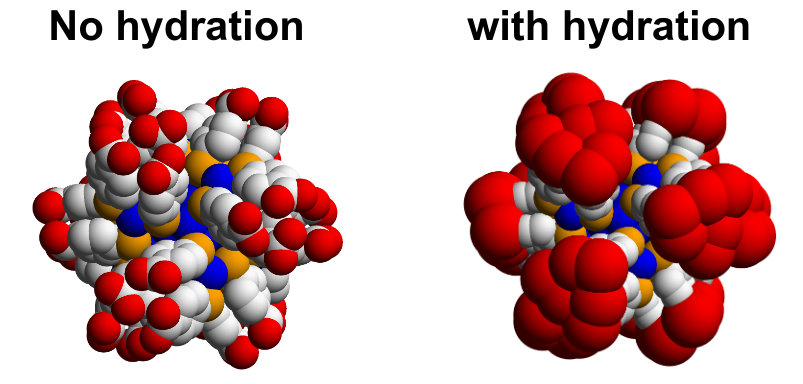

The partial specific volume is \(\bf{\text{highly solvent dependent}}\). The particle always carries along a solvation shell (adding to its size). The shell also changes the density, and because the size has change, the friction also changes.

PSV is quite hard to compute experimentally. For nucleic acids, for example, the estimation of \(\bar\nu\) is complicated by the fact that the PSV depends on:

-

base composition;

-

secondary structure;

-

solvation;

-

concentration of buffer ions, and;

-

identity of buffer ions.

The complicity of calculating PSV is shown in the equation below, which expresses how PSV is intimately related to the statistical-mechanical formulation of excess volume caused by the insertion of the solute into the solvent:

where \(v_{s}\) is the anhydrous solute volume, \(\delta\)_{w} is the number of waters in the hydration layer, \(v_{w}\) is the PSV of the water in the hydration later, and \(v_{0}\) is the PSV of the water in the bulk.

Intrinsic Viscosity

Macromolecules can alter the viscosity of a solvent. Linear polymers produce the greatest effects (unfolded polypeptide chains, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates).

Suppose we have a pure solvent with viscosity, \(\eta_{0}\), and a macromolecule of concentration, \(c\). The \(\bf{\text{measured viscosity}}\) would then be:

The \(\bf{\text{relative viscosity}}\) will be the ratio of measured to solvent viscosity:

The \(\bf{\text{specific viscosity}}\) is a measure of the effect the macromolecule has:

Therefore, when apprximated to the first order, the \(\bf{\text{intrinsic viscosity}}\) is then:

The intrinsic viscosity will have units of cm\(^{3}\)/g.

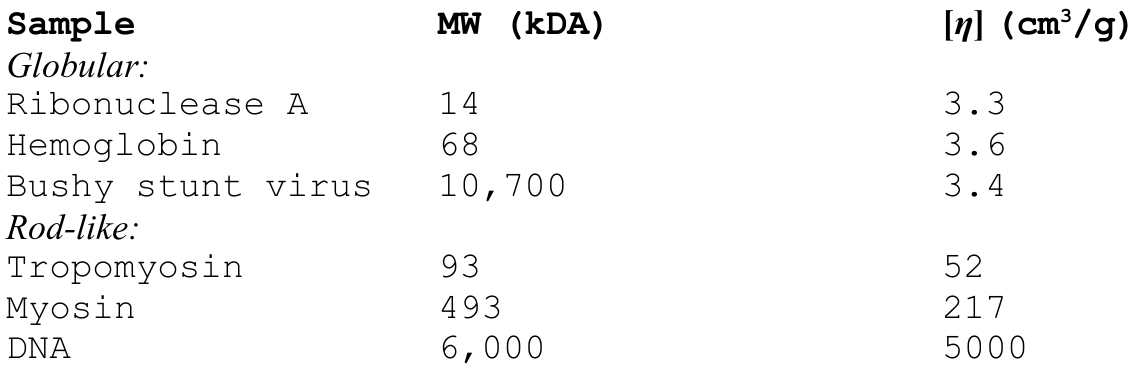

Note that intrinsic viscosity is not sensitive to molecular weight, but rather, it is exquisitely sensitive to the shape of the molecule. For example, consider a macromolecule that is a hydrated sphere. The intrinsic vicosity can be written as:

where \(V_{h}\) is the volume of the hydrated sphere, \(N_{A}\) is Avogadro's number, and \(M\) is the sphere's mass.We can see here that globular molecules of any size will have the same approximate intrinsic viscosity. Rod-like molcules, on the other hand, can have massive intrinsic viscosities. Consider the table below.

Measuring the intrinsic viscosity can allow you to monitor the unfolding of approximately spherical globular proteins. How can you measure \([\eta]\)? The viscosity of a solution can be measured by:

-

Cannon-Ubbelohde type viscometers;

-

rotating cylinder viscometer;

-

on-line differential viscometers (following a SEC seperation), or;

-

PDB or bead model computions.

The following information will focus on the physical properties of the hydrodyanmic parameters relavent to AUC.

TL;DR Hydrodynamic Parameteres

Frictional Coefficient: the proportionality between particle velocity and frictional resistance.

Sedimentation Coefficient: rate of velocity of a particle per unit acceleration.

Translational Diffusion Coefficient: thermal motion of molecules in solution causing them to move when when not subjected to an external force.

Rotational Diffusion:

Intrinsic Viscosity:

Sedimentation

Sedimentation is a widely used hydrodynamic technique using ultracentrifugation. There are two types of sedimentation experiments (described [here]/types): 1) where the velocity is measured, and 2) where, at equilibrium, the concentration distribution is measured.

Consider a particle of mass, \(m\), spun with an angular velocity, \(\omega\), at a distance from the axis of rotation, \(r\). The moleculer mass of this particle is described by \(M = mN_{A}\), where \(N_{A}\) is Avogadro's number. It has a partial specific volume, \(\nu\), and a density, \(\rho\). The particle will displace the mass of the solvent, creating its effective bouyant mass as:

This force now produces a velocity, which is resisted by a frictional force:

In a steady state situation (sum of forces is zero), we can define the sedimentation coefficient as the velocity of the particle per unit acceleration:

This coefficent, \(S\), has units of seconds (s), and are typically in the range of \(10^{-13}\) s to \(10^{-10}\). For ease, the value of \(1 \times 10^{-13}\) s is equal to 1 Svedberg (S).

Translational Diffusion Coefficient

{width="300"align=right)

{width="300"align=right)

\(\textbf{FICK'S LAWS OF DIFFUSION}\)

Fick's First Law states that the flux, \(\bf{J}\), of matter across an imaginary surface per unit area and per time unit is proportional to the concentration gradient and the diffusion coefficient:

Fick's second law comes out of this through an expansion in a Taylor series about x:

Fick's second law comes out of this through an expansion in a Taylor series about x:

The solution to Fick's Second Law for a situation with a spike of concentration, \(c\), at \(x=x_{0}\) and zero concentration everywhere else, is:

\(\textbf{FRICTIONAL RESISTANCE AND BROWNIAM MOTION}\)

\(\textbf{MEASURING DIFFUSION}\)

DYNAMIC LASER LIGHT SCATTERING:

FLUORESCENCE PHOTO-BLEACHING:

PULSED FIELD GRADIENT NMR:

We can measure diffusion in several different ways.

-

Boundary Method

-

Dynamic Light Scattering

-

Fluorescnece Correlation Spectroscopy

-

Sedimentation Velocity

Rotational Diffusion Coefficients and Relaxation Times

Intrinsic Viscosity

Solvent Density and Partial Specific Volume

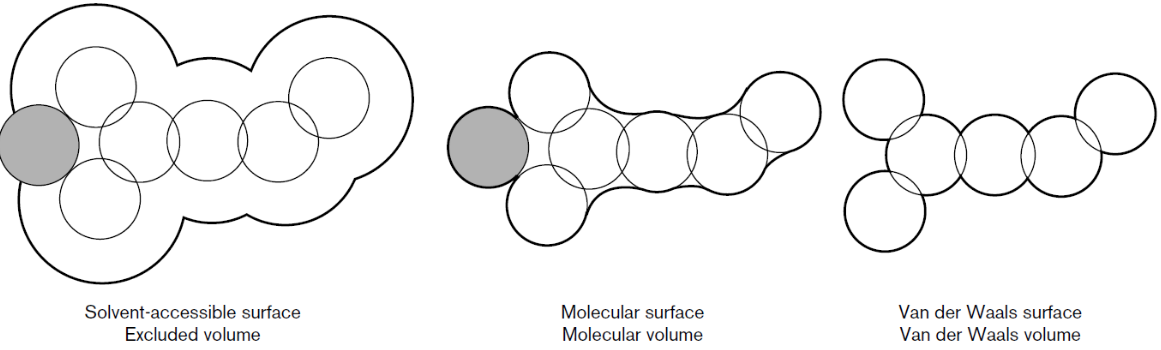

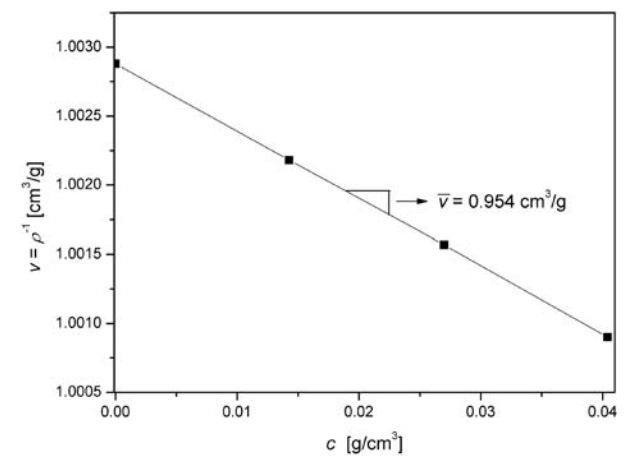

The partial specific volume (PSV), \(\bar\nu\), is the inverse of the particles density, \(\rho\). Specifically, the PSV is defined as the volume increase obtained if 1 gram of solute is added to an infinite amount of solvent. Knowing this parameter precisely is cruicial for the interpretation of sedimentation data. For proteins, it is common to assume the PSV as approximately 0.73 cm\(^{3}\)/g.

The best way to measure PSV is by using the Kratky density balance. For the pure solvent and for three solutions with different concentrations of the solute, the absolute densities can be measured. The PSV, the reciprocal of density, can be plotted as a function of concentration, \(c\).The slope of a regression line will yield the PSV of the solute.

Another method to determine solute density is through the determination of particle densities in AUC density gradients. Will be discussed later.

Polybutyl acrylate latex, water, 25C. Measured using Kratky density balance. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/b137083.pdf

Page 56